author: Carmen Bernier-Grand

Six children are playing in a city park in an ethnically and linguistically mixed neighborhood that appears to be in Brooklyn or the Bronx.

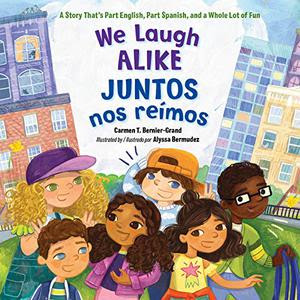

On the cover, the first thing young readers will see is a group of six young friends. Their varying skin tones, eye colors and hairstyles hint of their ethnicities, and they are laughing together. On the first few pages, the two groups of children haven’t yet met.

At the story’s beginning, the two groups are separate: three are hablantes and three are English-speakers, and neither understands the others’ language. The Spanish-speakers have a soccer ball and the English-speakers have a baseball. On beginning double-page spreads with the English-speakers (and text) on the left, and the hablantes (and Spanish text) on the right, both groups of children cautiously observe each other. As each listens to the words the others sing and watches the rhythms as they dance and jump rope—still not comprehending the words but noticing how alike the two groups play—they gesture to the others to join them.

And they do. Soon, the text evolves as well: While at the beginning, each language is on a separate page that matches that of the particular speakers, as they begin to play together, both Spanish and English in the text come together as well. Towards the end, the children jump rope (“double Dutch”) and count from one to twelve in alternating Spanish and English. Afterwards, they’re thrilled:

¡Ja! ¡Ja! ¡Ja!

¡Contamos en inglés!

Ha! Ha! Ha!

We counted in Spanish!

¡Ja! ¡Ja! ¡Ja!

Juntos nos reímos.

Ha! Ha! Ha!

We laugh alike.

One of the brilliant cultural markers here (and a clue to the care and empathy of the author, who may be writing from her own culture) is that the Spanish and English are not word-for-word translations of each other. Rather, Bernier-Grand presents the two languages as idiomatic: This is the way some kids think and talk in Spanish and this is the way some kids think and talk in English. So the title, for instance, “We laugh alike” becomes, in Spanish, “together we laugh.” If the translations from one language to the other here were literal, they would have “sounded” awkward.

In the beginning, English and Spanish text occupy separate pages, with each language “belonging” to the children who speak it. As the children begin to play together, Spanish and English texts also begin to come together. By the end, the children have become friends, their images fill the spreads, and the author flips the languages: the “English-speakers” wave good-bye with “¡Hasta mañana, amigos!” and the “Spanish-speakers,” with “See you tomorrow!”

It would be a mistake to assume that each “thought” that passes between the Spanish-speaking and English-speaking children is a translation of the other. While the two groups of friends come together and get to know each other, their initial narratives also voice their linguistic and cultural misunderstandings:

As the English-speaking children watch the Spanish-speaking children jump rope, they think, “They know how to jump rope! But we don’t understand their rhyme.” And the hablantes think, “Nuestra rima los invita a saltar con nosotros, pero no nos hacen caso.” (“Our rhyme invites them to jump with us, but they ignore us.”)

But as six kids start to interact, laughter and play become their “social” language—and they learn some of each other’s blended spoken language as well.

Bermudez’s computer-generated art, using scanned textures and bold, bright colors, is perfect. On vivid green-grass or yellow backgrounds, the children’s joy is palpable. Chasing each other on the Merry-go-round, dizzily falling down laughing, making dandelion crowns, counting to twelve inside a spinning double-Dutch rope, laughing so hard they have to hold their bellies—it may be difficult for a moment for young readers to discern which kids are the Spanish-speakers and which ones are the English-speakers. Which is just the point.

Unlike a lot of picture books, there is no conflict here that calls for resolution—and no adults are necessary to “teach” anyone anything.

We Laugh Alike / Juntos nos reímos is a celebration of friendship across language and culture.

*Highly recommended for all home, classroom, and library collections.

—Beverly Slapin

(published 3/31/21)

[Note: Carmen Bernier-Grand is a talented bilingual poet and storyteller who understands and appreciates children. ¡Bienvenida, Carmen!]