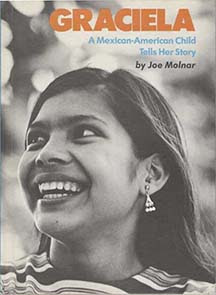

Franklin Watts, 1972

grades 3-up

Mexican American

Graciela is the first of three “photo-and-tape”

books by Joe Molnar, an elementary-school teacher who later decided to devote

himself to photojournalism. Inspired by the civil rights movement, he created a

series of books that told the lives of minority children in their own words.

With portable tape recorder and camera, he traveled the country, meeting with

families, shooting photos and listening to what the children had to say about

their own lives.

Through a social

worker in Brownsville, Texas, Molnar met Graciela and her large, hardworking

Mexican-American family.*

The text of the book, he writes, is based on tape recordings of conversations

with Graciela. Most of the black-and-white photos, naturally lit, were not

posed; and what makes this book important is that the words are clearly

Graciela’s, with very little filtering by the author.

Twelve-year-old

Graciela, her parents and her seven brothers and two sisters are a close-knit

family who spend part of the year at home in Texas and part of the year in

Michigan, working as migrant agricultural workers. Initial photos show Graciela

hanging out with her family, working with her mother in the kitchen, and taking

care of and playing with the baby. It’s clear that this family enjoys being together.

But Graciela’s

family’s lives are difficult, sometimes harrowing. When her three-year-old

brother is hit by a motorcycle, “the hospital said we owed them two hundred

dollars and Abel would have to stay there until we paid. I got very upset when

I heard that and thought the hospital was ignorant and mean. But later, on the

telephone, the hospital said yes, we could take him home and we brought Abel

home the next day.”

At the beginning

of June, Graciela’s family heads north to Michigan, where they work the fields

to try to earn the little that will sustain them when they return to Texas. “School

isn’t over yet,” Graciela says, “but we have to go because we need the money.

My little brothers will be able to finish their classes in Michigan for the

month of June, but the rest of us won’t.”

When they get to

Michigan, the large family has to live in a two-room house with only a

two-burner stove and without an oven or even running water. Graciela

matter-of-factly describes the work:

My mother and me, we go out to one field.

My father, Eleazar, Irma, and María go to another field. They pick tomatoes,

watermelons, beans, cucumbers, squash, and pickles. Pickles are the worst,

because you have to be bending down all the time and get all wet, pickle plants

have a lot of water. My mother and me, we pick cauliflower. We get a big bunch

and separate them and put them in baskets.

We all start at seven in the morning and

work until noon. Then we go back to the house for lunch or sometimes eat in the

field. About one o’clock we start working again until four or five. We’re very

tired when we finish and come home, our wrists hurt and our hands. We get paid

a dollar fifty an hour.

While the

townspeople in Michigan are more-or-less friendly to them, Graciela says, back

in Texas her family has to contend with out-and-out racism at school,

especially from teachers. And, opposite a photo of Graciela somberly looking on

while her mother is talking on the phone, she describes her family’s financial

worries:

Sometimes my mother and

father worry a lot. They worry about sending us to school. They want very much

for us to finish school and not to have to take us out just so we can work.

They try their best to give us clothes and dress us up real good so we can go

to school neat and proud. They worry about feeding our family too. And getting

another bed so my little brother David doesn’t have to sleep on a mattress on

the floor. So they worry about money a lot. Right now we have enough to pay our

bills. We are paying off the house, and in two more years, it will belong to

us. And we are paying off our truck, we’re almost through with that and it’s a

big bill too, about ninety-five dollars a month. Our biggest worry right now is

how to pay the hospital for Abel. But we’ll be okay. We’ll manage.

The photos and

text in the rest of the book show Graciela and her sisters and brothers playing

“chase and hide-and-seek and a lot of games that we think up ourselves,”

dancing, and going to a carnival in Brownsville, a big town just across the

border from Mexico. And on the last page, a smiling, almost laughing, Graciela

is literally framed by her parents. “Sometimes I wish I was already in high

school or I wish I was already a nurse and working,” she says. “Then maybe I

could have a piano. I would study and learn how to play it real good. I would

play happy music. Music like it would make me feel everything is okay,

everything is going to be all right.”

For young

readers who are agricultural workers, Graciela

is a treasure. For young readers who cannot imagine what material poverty is

like or how their food arrives at the supermarket, Graciela can be an education in itself. In any event, I’d like to

see Graciela together with other excellent

picture books about the struggles of agricultural workers, such as Carmen

Bernier-Grand’s César: ¡Sí, Se puede!

Yes, We Can!, Kathleen Krull’s Harvesting

Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez, and Sarah Warren’s Dolores Huerta: A Hero to Migrant Workers.

Although Graciela is an older out-of-print book,

it is available and highly recommended.

—Beverly Slapin

(published 7/25/15)

*Joe Molnar, telephone interview with Julia L.

Mickenberg, May 29, 2006. In Julia L. Mickenberg and Philip Nel, Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of

Radical Children’s Literature. NYU Press, 2008.

Thank you for this chance to rediscover a wonderful portrait. I've been looking for more material on the Latino experience in the Midwest, and the experiences of Graciela's family in Michigan will be a welcome addition to my reading. Gracias!

ReplyDelete