Oaxaca has had a wood carving tradition since long before first contact; the products of this tradition—from sacred to practical to whimsical—have taken the forms of religious statuaries, cooking utensils, household instruments, children’s toys and the like. Fast-forward to the 1950s, when a shepherd named Manuel Jiménez from the town of Arrazola was carving little wood animals while grazing his sheep at Monte Albán. When a white guy who owned a folk art shop in Oaxaca City “discovered” Jiménez and offered to buy everything that he could produce, others started to imitate Jiménez’s style, and the craft spread to San Martín Tilcajete and La Unión.

At about the same time, the opening of the Mexican span of the Pan American Highway brought to Oaxaca an influx of tourists, whom folk art dealers realized would happily purchase both replicas of old carvings and work that had no longstanding cultural traditions. This beginning of the folk art woodcarving practice has brought construction of paved roads, schools and hospitals to the area, and has been an important source of cash income for the woodcarvers and their families. And it’s one of the crafts that have made the state of Oaxaca world famous.

Weill, an English teacher who is fluent in Spanish, spent a Fulbright Teacher Exchange year in Mexico City and travelled to Oaxaca on weekends. Initially drawn to its abundance of crafts, she later enrolled in a doctoral program, researching intercultural collaboration in folk art production—and what would result if artisans created what pleased them rather than what might appeal to potential buyers. She also wanted a platform, as she told me, to showcase the work of the artists and artisans in ways that would recognize their unique talents.

Weill’s academic work eventually became a cross-cultural collaborative art project with several folk art producing families in Oaxaca. If a project were to be collaborative as well as cross-cultural, Weill would find out, she would have to give up a lot of control and become “joined at the hip” with the families with whom she worked. And everyone would have an equal voice.

One of the results of this collaboration is a series of five adorable bilingual concept books that introduce the littlest learners to the alphabet, colors, counting, opposites, and animal sounds. Anyone who is able to sit still for a moment will thoroughly enjoy the brightly colored- and -patterned wooden animalitos, on highly saturated backgrounds that bring to mind the texture of plastered walls.

author: Cynthia Weill

artists: Armando Jiménez, Moisés Jiménez

Cinco Puntos Press, 2007, all grades

Mexican

The first in the series, ABeCedarios: Mexican Folk Art in English and Spanish, features well known animals (“the Elephant / el Elefante”), and rare (“the Quetzal / el Quetzal”), and imaginary ones (“the Unicorn / el Unicornio”), and one that is as yet “undiscovered” (the mysterious “X / el/la X,” a winged creature that breathes fire); as well as animals for which there are uniquely Spanish sounds (“el Chapulín” to demonstrate “ch,” “la Llama,” to show “ll,” “el Ñu” or “gnu,” and “el Zorro,” to depict “rr”). artists: Armando Jiménez, Moisés Jiménez

Cinco Puntos Press, 2007, all grades

Mexican

author: Cynthia Weill

artists: Martín Santiago, Quirino Santiago

Cinco Puntos Press, 2009, all grades

Mexican

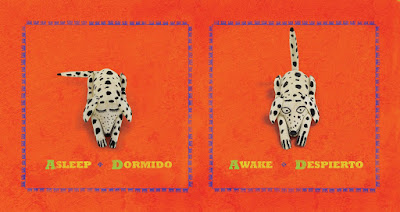

The second work, Opuestos: Mexican Folk Art Opposites in English and Spanish, depicts contrasting concepts on opposing pages (“asleep / dormido” and “awake / despierto”), sometimes depicting the same animal (“inside / adentro” and “outside / afuera” the frame) and sometimes showing a different animal or insect: The opposing concepts “high / alto” and “low / bajo,” show a butterfly on the upper left corner of the left page, while a dog, on the center of the right page, looks hungrily up at it; in another spread, two almost identical dogs, one with a “long / larga” tail faces one with a “short / corta” tail.

author: Cynthia Weill

author: Cynthia Weillartists: Rubí Fuentes, Efraín Broa, María Jiménez, Jesús Sosa, Angélica Vasquez, Carlomagno Pedro Martínez, Eleazar Morales, René Mandarín, Eloy Santiago, José Miguel Pacheco Aguero, María Jiménez

Cinco Puntos Press, 2011, all grades

Mexican

In the third librito, Colores de la Vida: Mexican Folk Art Colors in English and Spanish , the animals—done in different techniques this time—are mostly displayed on background colors that correspond to the animals themselves. So, for instance, two purple bunnies (with orange carrots, which add some contrast and realism) sit on and opposing a “purple / morado” background, and a glorious orange lion (with a full mane and what appear to be actual orange slices as ears and eyes) sits on an “orange / anaranjado” background. I especially like the question at the end (with a cow and her calf on a green background and the lettering on a blue background): Can you say all the colors in Spanish? / ¿Puedes nombrar todos los colores en inglés?

author: Cynthia Weill

author: Cynthia Weillartists: Guillermina Aguilar, Josefina Aguilar, Irene Aguilar, Concepción Aguilar

Cinco Puntos Press, 2012, all grades

Mexican

Unlike the others, Count Me In! A Parade of Mexican Folk Art Numbers in English and Spanish features all humans, decked out to participate in a festival called “Guelaguetza,” which is Zapotec for “to share.” Except for the initial two-page spread, which shows a line of people beginning the parade (Here comes the parade! / ¡Aquí viene el desfile!), all of the other illustrations (along with captions that will entice the youngest of listeners) land on the right-hand pages on solid backgrounds with only the numbers 1-10 in English and Spanish. Opposite “four / cuatro,” for instance, is this: The giants are my favorite! See the person wearing the costume peeking through from inside? / ¡A mí me encantan los gigantes! ¿Ves a la persona que lleva el disfraz mirándonos desde adentro?

author: Cynthia Weill

author: Cynthia Weillartists: Rubí Fuentes, Efraín Broa

Cinco Puntos Press, 2016, all grades

Mexican

Bilingual, colorful, inviting, absolutely adorable—and definitely child-centric—these libritos will capture and hold the attention of the littlest to the biggest kids (and adults alike—I keep coming back to them, and I’m known to be hard to please). All are highly recommended.

—Beverly Slapin

(published 6/1/16)

*Highly recommended for all home, classroom and library collections.

[Reviewer's note: I want to share with readers some information about how this project's collaborative plan becomes a reality. Cynthia Weill and the artists work together for between two and four years to produce each book. (Cynthia mentioned to me that her role often includes babysitting so that the artist families can concentrate on their craft.) She pays the artists market rate for their work, which she then donates to the Field Museum of Chicago. After each book has been produced, Cinco Puntos Press gives each artist family 100 copies of the book that features their work.]

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome all thoughtful comments. We will not accept racist, sexist, or otherwise mean-spirited posts. Thank you.